An attempt at defining intelligence

Intelligence is a highly valued aspect of human behavior, which is often linked to positive outcomes, in contrast to the irrational actions typically associated with stupidity. In modern society, the importance of physical strength and beauty fades in comparison to intellectual prowess, which shapes complex social norms and advances technology. Now, as we stand on the brink of giving this sacred gift to machines —a development poised to surpass our own capabilities— defining and measuring intelligence remains a challenge that has puzzled researchers for centuries.

The challenge in defining intelligence stems from its manifestation across a broad spectrum of human activities and behaviors, rooted in the brain’s complex mechanisms. This diversity makes it nearly impossible for a single theory to fully encapsulate what intelligence entails. Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences attempts to tackle this by categorizing intelligence into distinct dimensions, such as Linguistic, Logical-Mathematical, and Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence, among others. Yet, even within these categories, individuals demonstrate intelligence in vastly different ways, as illustrated by the distinct capabilities of surgeons and professional climbers under the umbrella of Bodily-Kinesthetic intelligence. This variation suggests that any attempt to categorize intelligence might inherently simplify its complexity. Indeed, the endeavor to fully understand and define intelligence may reveal a paradox: our intelligence might not be sufficient to grasp the entirety of its own potential and diversity.

One approach to circumnavigate the challenges of defining intelligence is to conceptualize it as a capacity for creating mental representations rather than a capability to achieve specific behaviors. These mental representations are necessary for intelligent behaviors to manifest. This capacity provides boundless possibilities to comprehend our environment and effect change. Thus, I propose defining intelligence as:

The capacity to construct representations of our environment, others, and ourselves for the purpose of solving problems and planning actions to achieve novel objectives.

This definition suggests mechanisms within the brain that build representations to enable meaningful actions. This differs from behaviorist or functionalist theories and aligns more with constructivist theories. However, the abstract nature of these representations poses a significant challenge: how do we verify their existence within our neural architecture? Moreover, the rationale for categorizing representations into three distinct areas—environment, other beings, and self—warrants further exploration, as does the development of functional assessments aligned with this conceptualization of intelligence. The ensuing discussion will address these critiques and explore open questions, aiming to refine our understanding of intelligence.

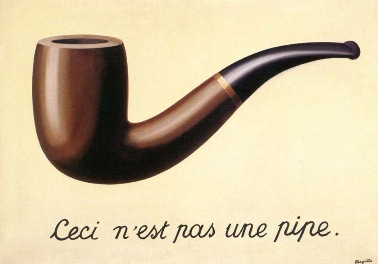

The word 'representation' is derived from the Latin 'repraesentare,' which, according to the Oxford Reference, means depicting or ‘making present’ something which is absent (e.g., people, places, events, or abstractions) in a different form: as in paintings, photographs, films, or language, rather than as a replica. This nuanced understanding is crucial in discussing intelligence, where mental representations serve a similar purpose. René Magritte’s iconic painting, “The Treachery of Images,” embodies this concept by reminding us that the representation is not the object itself, a distinction we often overlook. In the early 20th century, Alfred Korzybski reminds us of his famous dictum that "the map is not the territory" in his theory of language called General Semantics. However, this very convenient shortcut allows us to navigate our world, solve problems, and plan for the future, underscoring the importance of representations in the mechanisms of intelligence. However, as Magritte elegantly illustrates, these representations, while essential, are not direct replicas of reality but rather interpretations or constructions that our minds create to make sense of the world around us.

Drawing on the concept of representation, as beautifully exemplified by René Magritte's 'The Treachery of Images,' we understand that our brain's capacity to construct neural representations is foundational to our intelligence. These representations, formed from our sensory experiences, are not static but dynamic, evolving over time to encapsulate complex life experiences. They can be stored and retrieved from our memory over a lifetime. The challenge lies in understanding the brain's algorithms for combining them—a process we hypothesize to involve non-commutative operators, hinting at the sequential nature of cognitive processing and the emergence of temporal perception (more on this hypothesis in a following blog post).

Moreover, our ability to share and translate these internal experiences into external expressions—whether through language, art, or other forms of communication—reveals both the universality and the unique cultural interpretation of these representations (see Figure 2). Symbols, whether words or images, act as conduits for these mental constructs, bridging internal cognition with external understanding. However, the ease of language acquisition compared to the mastery of writing skills or sculpting and painting illustrates the varied challenges in translating mental representations into different forms of expression.

![“A transformation mask, also known as an opening mask, is a type of mask used by indigenous people of the Northwest Coast of North America and Alaska in ritual dances.” (Reference: [] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transformationmask )](https://gamarceau.ghost.io/content/images/2024/03/DraggedImage-4-1.png)

The proposed definition emphasizes the nuanced differentiation of representations into three broad distinct categories: the environment, other living beings, and ourselves. This division is predicated on the seemingly universal and self-evident hypothesis that our cognitive architecture inherently distinguishes us from our surroundings and other entities. For instance, my excitement about discovering a new mathematics book doesn't automatically translate to my wife sharing the same thrill. This delineation between my neural representations of personal joy and my perception of my wife's potential indifference underscores a critical cognitive boundary. Such distinctions in neural encoding ensure that our sense of self and our understanding of others maintain their separateness, preserving individuality amidst a natural human desire for connection and empathy. The underlying hypothesis suggests that this compartmentalization is not merely a byproduct of social or cultural conditioning but is fundamentally embedded within our neural circuitry, reflecting a sophisticated mechanism evolved to navigate complex social landscapes from childhood to adulthood.

The nuanced distinction between our internal sense of self and the external perceptions of group identities allows us to craft our identities over time, weaving together the cultural narratives of our communities with our personal experiences and self-conceptions. This intricate alignment fosters a sense of belonging, enabling us to experience various degrees of connection with others. These connections typically resonate more deeply within human relationships than between humans and animals, attributed to the sophisticated and multifaceted nature of human interactions. However, this complexity can sometimes be overwhelming, particularly when an individual's self-perception becomes deeply entwined with a group identity, especially one characterized by a strong, cohesive ethos led by a charismatic figure. In such scenarios, the allure of group conformity can overshadow personal individuality, with group symbols like logos and propaganda reshaping one's self-image in profound ways.

Conversely, some individuals may find solace in the simplicity of animal companionship, where the dynamics of identity and influence are markedly less complex. The straightforward nature of human-animal relationships offers a unique reprieve, as animals, with their uncomplicated responses, are less likely to significantly alter one's self-representation. Instead, individuals might appreciate the opportunity to shape the perceptions of their pets, enjoying a sense of influence and connection unburdened by the complexities of human social constructs.

In the context of navigating these diverse relationships, intelligence manifests as the ability to maintain a balance between our internal narratives and the external influences of others. This balance is crucial for fostering healthy relationships, preserving our sense of self, and navigating the intricate social landscapes we inhabit.

The distinction between our internal representations and those of the environment is different. Our inner representations of our needs align with the representations of the resources available to our senses to fulfill these needs. Getting the resource becomes an objective that requires planning a sequence of actions, sometimes with intermediate goals such as building tools. With experience, we can simulate the transformation of our representations of the world to better plan without causing energy spending. We refer to this capability as a world model.

We can also consider other humans or animals as tools to achieve our objective. However, contrary to the previous context, they cannot alter the representations of self since they are considered entities that cannot communicate representations. When this happens at the societal level, it leads to a group of people exploiting another group by enforcing that mental representations associated with both groups are segregated. The modern society aims to favor universal individual representations at the expense of incompatible group representations. These universal individual representations rely on our humanity: the hypothesis that we all share common representations defined by our human condition. These universal representations could support the lingua universalis of the unfinished tower of Babel.

The challenge in redefining intelligence lies not in its functionality but in the broad potential of its mechanism-based nature, which is actually its strength. Traditional definitions fall short by not accommodating the wide range of behaviors indicative of intelligence. This is the crux of the dilemma in defining intelligence: opting for a behavioral approach limits the scope, whereas a focus on underlying mechanisms acknowledges the potential for generating myriad intelligent behaviors. Language serves as a prime example of this, with its infinite possibilities for expression and persuasion. Therefore, it becomes evident that intelligence cannot be universally assessed; instead, we can only evaluate an individual's adaptability and the sophistication of their mental representations within specific contexts. This approach necessitates a clear articulation of what each "intelligence" test measures and its intended purpose. For instance, in assessing Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence, we might evaluate a climber's ability to navigate routes that typify a particular climbing style. Ultimately, an individual's ability to excel across diverse tests might offer a composite view of intelligence, albeit with the understanding that each assessment captures only a facet of their cognitive capabilities.

As we embark on this unprecedented journey to bestow machines with what we consider a sacred gift, the endeavor to define and measure intelligence becomes not just a scientific challenge but a philosophical quest that has intrigued and confounded humanity for centuries. How will this quest evolve as intelligence, once the domain of living beings, transitions into the realm of the artificial?